EB-5 Capital Diversion: How a Credit Union Lending Model Can Be Denied

The Core Issue: When EB-5 capital is expended, it generates economic multiplier effects. When capital is lent, it creates a financial obligation, not economic impact.

Meet a well-meaning group of entrepreneurs and investors who saw a genuine need and tried to address it through the EB-5 program. Their story illustrates how even well-intentioned projects can fail when applicants ignore foundational logic and try to ignore USCIS regulations.

The Setting: A Lending Desert in Rural Texas

Like many rural areas across the United States, a small county in Texas was experiencing what researchers call a “lending desert”—a region where access to credit had become scarce, and banking institutions were few and far between. When a census tract lacks bank or credit union branches within a 10-mile radius, residents and small businesses struggle to access the capital they need to thrive. Rural consumers in such areas travel nearly twice as far to banking services and face higher costs for credit. Some turn to predatory alternatives like payday lenders. Others simply do without.

This particular Texas county had once had a credit union serving the community, but it had closed a year earlier due to financial difficulties. The closure left hundreds of families and small business owners without access to reliable lending. The opportunity cost was real: Studies show that when a financial institution closes its doors, business lending in that region drops by an average of $453,000 annually for approximately six years.

Young entrepreneurs couldn’t get startup capital. Farmers couldn’t access seasonal credit lines. Families couldn’t qualify for mortgages.

Then an opportunity emerged: the old credit union building could reopen. But it would require significant capital to restart operations—not just to restore the physical location, but to rebuild the credit union’s capital base, invest in modern technology infrastructure, hire experienced staff, and recapitalize the lending portfolio.

The Plan: $13 Million to Rebuild, Including $5.6 Million from EB-5 Investors. The entrepreneurs developed an ambitious and seemingly reasonable plan. They would raise $13 million total, allocataed as follows:

- $11.75 million: Recapitalize the credit union to restore it to a sound financial position and establish the lending base

- $0.95 million: Fund initial operational costs (staffing, technology, compliance, regulatory capital requirements)

- $0.3 million: Expansion planning for eventual countywide service

More than half would come from traditional venture capital while $5 Million would come from EB-5 immigrant investors. The investors would purchase shares of the credit union’s capital stock, and in return, they would receive green cards based on the job creation requirements of the EB-5 program.

On the surface, this seemed to be a reasonable costruct: the project was in a rural area (qualifying as a Targeted Employment Area), it addressed a genuine community need, it had a clear business purpose, and it promised economic benefits. What could be wrong?

Everything. The entire construct is counter to fundamental EB-5 policy.

To understand why this credit union project fails EB-5 requirements, the Matter of Izummi AAO (Administrative Appeals Office) precedent decision is the place to start. It still governs adjudications today.

The Izummi Precedent

In Matter of Izummi, the AAO established a foundational rule that has never been overturned:

“The full amount of money must be made available to the business(es) most closely responsible for creating the employment upon which the petition is based. The Service does not wish to encourage the creation of layer upon layer of ‘holding companies’ or ‘parent companies,’ with each business taking its cut and the ultimate employer seeing very little of the aliens’ money.”

More specifically, the AAO emphasized:”The full amount of money must be made available to the business(es) most closely responsible for creating the employment upon which the petition is based. The Service does not wish to encourage the creation of layer upon layer of ‘holding companies’ or ‘parent companies,’ with each business taking its cut and the ultimate employer seeing very little of the aliens’ money.”

This was not bureaucratic overreach. The AAO was addressing a real concern: investors were creating complex structures where EB-5 capital would be filtered through multiple intermediaries—partnerships, limited companies, investment companies—and by the time it reached the actual job-creating entity, much of it had been consumed by administrative fees, holding company expenses, and other diversions.

The Principle: EB-5 capital cannot be diverted away from the entities most closely responsible for creating jobs.

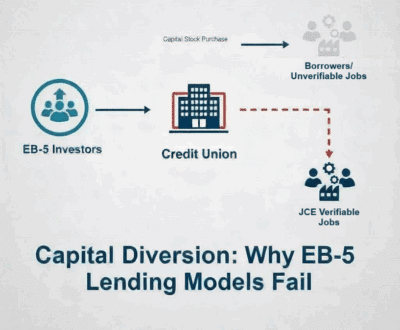

How the Credit Union Model Violates This Principle

With an EB-5 capital investment in the credit union project:

Step 1: Investors Purchase Credit Union Capital Stock

- EB-5 investors (combined) send $12 million to purchase shares of the credit union’s capital stock

- This money becomes regulatory capital on the credit union’s balance sheet

- The funds are now in the credit union but not unavailable for direct deployment to the job creating entity.

Step 2: The Credit Union’s Business is Lending

- The credit union’s core activity is making loans to its members and businesses

- The credit union lends this money to borrowers at its discretion

- Based on the credit union’s definition of direct job creation, these borrowers—the farmers, small business owners, entrepreneurs—are the actual job-creating entities.

Step 3: Borrowers Receive Loans (Not Investment Capital)

- A farmer borrows $100,000 to expand operations

- A small business owner borrows $250,000 to purchase equipment

- They receive debt instruments with repayment obligations, not equity investments or capital contributions

- They are expected to repay these loans with interest

The Problem

The EB-5 capital never reaches the actual job-creating entity (the credit union). Borrowers remain in the credit union’s capital structure, segregated from the business, as surrogate JCE’s.

This is capital diversion in its purest form.

Why This Matters: A More Recent Confirmation

Matter of W-Z- (AAO Dec. 10, 2018):

“The Administrative Appeals Office held that the investor could not satisfy the required investment amount where part of the invested funds were diverted away from the job-creating entity.”

A Compliant Real Estate Development Project

- Developers raise $10 million in EB-5 capital

- Developers spend that capital on documented construction costs:

- Concrete, steel, lumber: $4 million

- Labor (construction workers): $3 million

- Equipment and machinery: $2 million

- Design and engineering: $1 million

- These expenditures flow through supply chains, creating indirect jobs

This works because EB-5 capital is spent—it enters the economy permanently and cannot be recovered. The money paid to construction workers, suppliers, and equipment vendors remains in the local economy, creating economic impact.

The Credit Union Lending Model (Non-Compliant)

- Investors provide $5.6 million to the credit union via EB-5 capital stock purchase

- The credit union lends $11.75 million to borrowers (or some portion of it)

- The EB-5 capital is not spent—it is loaned

- The borrower receives a debt obligation requiring repayment with interest

- The credit union expects to recover this capital (plus interest) when the loan is repaid

Because the EB-5 capital is a loan (not a final expenditure), it creates no direct economic impact in the input-output models used to calculate job creation

Any diversion of funds away from the job-creating entity disqualifies that portion of the investment. The principle remains unchanged and unchallenged.

In the credit union scenario, it’s not a partial capital diversion from the actual job-creating entity to the borrowers’ businesses. The EB-5 capital stock purchase keeps the money in the credit union’s regulatory capital base, where it funds lending activity but does not directly enable verifiable, attributable job creation.

The Logical Problem: If You Can’t Guarantee the Jobs, You Can’t Claim Credit for Them

This client refused to consider that there might be a fundamental lack of logic in the credit union’s job creation model.

The credit union proposes that EB-5 investors should receive job creation credit based for the jobs that borrowers will create using loans from the credit union. But sometimes logic dictates a structure that is counter to what the client wants. Then, the choice becomes whether or not the applicant wants to risk outright denial. So, what were the issues with the model?

Problem #1: The Credit Union Cannot Control Borrower Behavior

When the credit union lends money to a farmer or small business owner, it cannot dictate how that money is used or what the outcomes will be. The borrower might:

- Use the loan for expansion, which creates new jobs ✓

- Use the loan to replace existing workers with automation, which eliminates jobs ✗

- Default on the loan, which creates no jobs at all ✗

- Use the loan to relocate an existing business from another state, which creates “relocated jobs” (explicitly prohibited under the RIA 2022) ✗

The credit union’s business plan assumes borrowers will create jobs as promised. But USCIS has made clear through decades of precedent that assumptions are not enough. The proposal must be credible, detailed, and verifiable.

Problem #2: No Mechanism for Verification

A legitimate EB-5 project must provide USCIS with documentary evidence that jobs will be created. For a construction project, this means:

- Construction budgets showing dollar amounts and line items

- Contracts with general contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers

- Economic impact studies using validated methodologies (RIMS II, IMPLAN) that calculate jobs from documented expenditures

- Payroll records and W-2 documentation once jobs are created

- Oversight by a qualified Funds Administrator

For a credit union lending model, how does this work? Can the credit union provide more than:

- A list of anonymous borrowers who promise to create jobs?

- Contingent promises from borrowers that may never materialize?

- Economic models based on hypothetical lending to unknown businesses?There is no mechanism for the USCIS to verify that jobs will be created. And, there is no mechanism to verify, after the fact, that job creation actually occurred and that it was attributable to the EB-5 investment.

Problem #3: The Credit Union Cannot Guarantee Loan Volume

Here’s where the logic breaks down completely. The credit union’s job creation depends on:

- Making loans at all (discretionary)

- Making enough loans to generate the required job creation (beyond the credit union’s control)

- Those borrowers creating jobs (beyond the credit union’s control)

- Those jobs being new jobs (not relocated or replacing existing workers)

- All of this happening within the required timeframe (unknowable)

The credit union admits in its scenario that “there is no chance that the bank can hire enough full-time employees to satisfy the calculated direct job requirements.” So it is trying to claim credit for borrower jobs. But these fundamental questions preclude using this as an argument:

- What if the credit union doesn’t make enough loans?

- What if borrowers don’t create the projected jobs?

- What if job creation doesn’t materialize?

The answer: The EB-5 investors are faced with failed applications. They don’t get their green cards. Their investment is at risk—not as an EB-5 investment should be (in a viable business), but as a failed gamble on unknowable future behavior by third parties.

This is not investment logic. This is speculation.

The Legal Problem: EB-5 Capital Expenditure vs. Financial Intermediation

Beyond the logic problem lies a deeper legal principle that will ultimately doom this structure: EB-5 economic impact must flow from actual capital expenditures, not financial intermediation.

The distinction is fundamental: When EB-5 capital is expended, it generates economic multiplier effects. When capital is lent, it creates a financial obligation, not economic impact.

The RIA 2022 Misconception: Tenant Occupancy is About Real Estate, Not Lending

At this point, our clients may raise an objection: “But didn’t the RIA 2022 expand the types of jobs that can be counted? What about the new tenant occupancy provision?”

Yes, the RIA 2022 did make important changes to EB-5 job creation methodologies. But its tenant occupancy provision explicitly does not include lending models.

What the USCIS Actually Requires

USCIS Policy Manual is explicit: Capital must be deployed into “any commercial activity consistent with the purpose of the new commercial enterprise”, and it must be traceable through documented expenditures.

“In determining compliance with the job creation requirement under subparagraph (A)(ii), the Secretary of Homeland Security may include jobs estimated to be created under a methodology that attributes jobs to prospective tenants occupying commercial real estate created or improved by capital investments if the number of such jobs estimated to be created has been determined by an economically and statistically valid methodology and such jobs are not existing jobs that have been relocated.”– Immigration and Nationality Act § 203(b)(5)(E)(ii)(II)(aa), 8 U.S.C. § 1153(b)(5)(E)(ii)(II)(aa)

The policy is designed to prevent exactly what the credit union model proposes: Using EB-5 capital for financial intermediation (lending) and then claiming credit for the results of that lending, which are uncertain and unverifiable.

The issue with the credit union model is fundamentally one of logic and legal compliance. The structure’s failure is not because of a technicality or obscure regulation, but because it violates established EB-5 principles reaffirmed by the 2022 RIA (EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act (RIA) 2022).

Why Risk An RFE or a Denial?

An unworkable model benefits no one. We don;t want to tell our clients that the USCIS may reject their construct and they don’t want to hear it. In our experience, when we present this analysis to entrepreneurs who have invested significant time and money in developing an EB-5 project, we may meet resistance. But it is our due diligent responsibility to identify issues like this and to alert the client about the risks involved in submitting a noncompliant application. If, at that point they want to pursue their original model no matter what, we will oblige.

But it is usually better to hear it from us than in an outright USCIS denial. Even if clients don’t like what we have to to say, they will listen because they know it is better to hear it from us than risk an outright USCIS denial. Unrealistic plans often trigger Requests for Evidence (RFEs) or outright denials because they lack credibility.

Our Approach and Why It Is Different

We approach business plans, economic studies and RFE responses based on logic and the requirement for compliance with USCIS regulations and Policy Manual requirements. We don’t try to convince you that questionable structures might work or that the USCIS might overlook fundamental defects.

More importantly, we are willing to work with you to come up with a credible, reasonable and logical construct that the USCIS requires. And then we help you document it in accordance with USCIS requirements. We provide what is required by the USCIS:

The plan should contain a market analysis, including the names of competing businesses and their relative strengths and weaknesses, a comparison of the competition’s products and pricing structures, and a description of the target market and prospective customers of the new commercial enterprise. The plan should list the required permits and licenses obtained. If applicable, it should describe the manufacturing or production process, the materials required, and the supply sources.

The plan should detail any contracts executed for the supply of materials or the distribution of products. It should discuss the marketing strategy of the business, including pricing, advertising, and servicing. The plan should set forth the business’s organizational structure and its personnel’s experience. It should explain the business’s staffing requirements and contain a timetable for hiring, as well as job descriptions for all positions. It should contain sales, costs, and income projections and detail the basis of such projections.

-Matter of Ho, 22 I&N Dec. 206 (AAO 1998)

Most importantly, the business plan (EB5, L1A, E2, EB2 NIW) must be credible–ours are.

Contact Us For a Free Unvarnished Assessment of Your Project or RFE

References

Klasko Immigration Law Partners, “USCIS Reverses EB-5 Project Tenant Jobs” (2024)

Congress.gov, “EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 – H.R. 2901” (2022)

Baker Donelson, “Analysis of New EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022” (2022)

Green Card By Investment, “Tenant Occupancy – EB-5 Jobs” (2022)

EB5 Visa Investments, “How Job Creation Is Tracked and Verified in EB-5 Projects” (2025)

Klasko Immigration Law Partners, “EB-5 Investment and Bonds” (2024)

IIUSA, “New Job Creation and TEA Rules in the EB-5 Reform” (2022)

EB5 Investors Magazine, “Using Jobs from Construction Activity” (2017)

EB5 Affiliate Network, “EB-5 Job Creation: Construction & Operations” (2024)

PSU Insight @ Dickinson Law, “EB-5: Selling Citizenship?” (2025)

AILA, “USCIS Policy Guidance on Deployment of Capital” (2020)

Legal Services Incorporated, “Can I Direct EB-5 Investment Funds for Business Asset Purchase?” (2025)

Carolyn Lee PLLC, “EB-5 Investment At Risk and Sustaining Investment” (2022)

Darren Silver, “Job Creation is a Key Element to Successfully” (2017)

Lucidtext Blog, “Options for Investing in an Existing Business” (2011)

U.S. Department of Justice, “Matter of Izummi, 22 I&N Dec. 169 (AAO 1998)”

Philadelphia Federal Reserve, “U.S. Bank Branch Closures and Banking Deserts” (2024)

NCRC, “Small Business Lending Deserts and Oases” (2014)

CFPB, “Data Spotlight: Challenges in Rural Banking Access” (2022)

Fed Communities, “The Last Bank Branch Standing” (2025)

Credit Unions, “Why Do Banking Deserts Exist? How Can Credit Unions Fix Them?” (2025)

Andrew Van Leuven, “Locational Determinants of Lending Deserts in Rural US” (2023)

EB5 Visa Investments, “Approved Rural EB-5 Projects” (2025)